What we've learned in the past 22 years...Read Dr Bose's blog

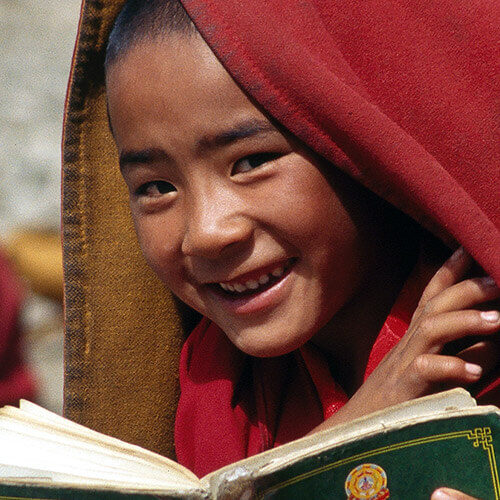

When I started Parikrma more than two decades ago, many well-wishers and journalists asked me what my long-term plan was. The truth is — in the early years of any non-profit, there is barely enough time to think of the next month, let alone the next 20 years. Dreaming 50 years ahead, without a corporate or foundation backing, felt almost arrogant. And yet, even then, I found myself saying — with a steadiness I did not quite feel — that Parikrma existed because no one should be condemned to an undignified life in the slums, and the only sustainable escape was through quality education.

When I started Parikrma more than two decades ago, many well-wishers and journalists asked me what my long-term plan was. The truth is — in the early years of any non-profit, there is barely enough time to think of the next month, let alone the next 20 years. Dreaming 50 years ahead, without a corporate or foundation backing, felt almost arrogant. And yet, even then, I found myself saying — with a steadiness I did not quite feel — that Parikrma existed because no one should be condemned to an undignified life in the slums, and the only sustainable escape was through quality education.

Twenty-two years later, that conviction remains unchanged. I have always believed that slums should not exist. Housing, sanitation, water supply — these are not merely infrastructure issues, they shape self-worth and possibility. I have seen girls feel humiliated standing in a line for a community toilet at 5 am while menstruating. I have seen sewage flood homes during monsoons, destroying schoolwork and books. I have seen five-year-olds queuing up at a tap with a plastic container instead of getting ready for school. Geography of birth becomes destiny — not because of lack of intelligence, but because of the physical environment.

I knew I did not have the expertise or bandwidth to solve the housing crisis. So I built schools instead — right next to the slums — to try and give children the mindset, qualifications and confidence to walk out of the slums by choice. Globally, this conversation is becoming urgent. A billion people today live in informal settlements. UN-Habitat calls this “the largest housing crisis in human history” and reiterates that housing is not shelter — it is dignity.

We must, therefore, acknowledge what data and experience both show us: learning outcomes correlate with living conditions. When a child grows up amidst alcoholism, fights, noise, lack of water, lack of electricity — homework will suffer. Behaviour will suffer. Confidence will suffer. And, yet, we continue to judge slum children academically as if they were all growing up in equal circumstances.

Over the last two years I have tracked the Jaga Mission in Odisha — the world’s largest slum redevelopment initiative. Every relocation was done within 1 km of original habitation, keeping livelihoods and communities intact. All through, communities were consulted, Slum Dweller Associations were formed, and women were made joint land owners. Land became proof of identity — but could not be resold. Infrastructure gaps were mapped and streetlights, playgrounds, piped water and individual toilets were ensured. It is an exemplary model of participatory redevelopment. And yet, I believe — without bias but with deep knowledge — that what we do at Parikrma is the other irreplaceable half of the solution.

We have 2000 children currently studying with us, and 1700 alumni. Slowly but steadily, they are beginning to leave the slums. They are renting modest apartments, some are buying small homes, many are inviting us to housewarming ceremonies. They are holding jobs in software engineering, nursing, hospitality, customer service — and they are choosing dignity.

Slum redevelopment is essential — it repairs the present. Education of slum children is equally essential — it transforms the future.

For me, the work feels complete only when our children voluntarily leave the geography of deprivation and choose the geography of possibility. When they can stand shoulder to shoulder with anyone, anywhere. When they can begin life not as survivors, but as citizens with agency.

That is what Parikrma has tried to do for 22 years.

We do not simply change housing. We change horizons.